What You Get in a Serving of Prunes

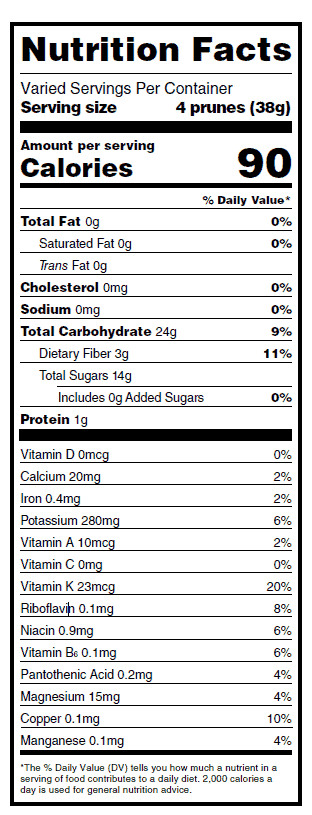

Prunes are a good-for-you snack that offers a wealth of nutrients and health benefits related to gut health, bone health, heart health and more. A serving of four to six prunes (38-40 grams) is around 100 calories and is deliciously satisfying, with a sweet flavor, luxurious texture and …

- 3 grams of fiber, or 11% of the Daily Value (DV), which helps regulate the body’s use of sugars, helping to keep hunger and blood sugar in check.

- 24 grams of carbohydrates (9% DV), which provide energy for bodies to perform at their best.

- 20% of the DV for vitamin K, which is important for blood clotting and bone metabolism.

- 6% of the DV for potassium, an important mineral that may play a role in maintaining healthy bones and is important for muscle contractions and fluid balance.

- Other important vitamins and minerals like magnesium, boron, riboflavin, niacin, and vitamin B6.

- A low Glycemic Index (GI) of 29.

- No added sugar, cholesterol, sodium or fat … and how many snacks can make that claim?

Why Eat a Few Prunes Every Day?

More than 70 peer-reviewed, published studies have examined prune consumption in relation to healthy digestion, gut health, bone health, heart health, weight management, satiety, and more. A few highlights:

Overall health benefits of prunes

A 2018 review study on the health effects of prunes and fresh plums showed promising results on their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and memory-improving characteristics. The authors added that plum and prune consumption is associated with improved cognitive function, bone health indicators and cardiovascular risk factors.

Improved digestion and gut health

In a study published in 2022, drinking prune juice helped alleviate constipation without side effects. A 2019 study had similar findings with whole prunes. These built on earlier studies concluding that prunes worked better than psyllium, the main ingredient in many over-the-counter laxatives, for relieving constipation. Most recently, a 12-month study among older women eating prunes daily showed a notable increase in a certain type of beneficial gut bacteria.

Maintaining digestive health is an important component of overall well-being. Prunes contribute to digestive health in several ways through the provision of dietary fiber, sorbitol and polyphenols with the potential to change the gut microbiome.

Prunes are the only natural, whole fruit to achieve this authorized health claim in Europe: Prunes contribute to normal bowel function when 100 g (about 10) are eaten daily (European Food Safety Authority). Research also suggests that eating 80 g (about 8) prunes may offer the same desired effect (Lever E et al 2018).

Responses to a bowel habits questionnaire used in research with postmenopausal women eating 0 g, 50 g or 100 g of prunes for 6 months indicated that moderate consumption had no undesirable changes in bowel function. Constipation ratings were higher in the control group, suggesting that prunes may decrease discomfort associated with bowel movements (Shamloufard P, Kern M, Hooshmand et al 2016).

Research with subjects with chronic constipation compared the effects of prunes (50 g twice daily) with psyllium (11 g daily) matched for 6 g of fiber, and discovered that prunes were safe, palatable and “more effective than psyllium for the treatment of mild to moderate constipation and should be considered as first line therapy.” (Attaluri A, Donahoe R, Valestin J, Brown K, Rao S. et al 2011).

A randomized control trial in healthy adults with low fiber intake looked at the effect of prunes on the gut microbiota in addition to other gastrointestinal functions. Participants were randomized into a control group (0 prunes), 80 g or 120 g prunes. There was an increase in Bifidobacteria in the 120 g prune group although there were no significant changes in the other bacteria measured. (Lever E et al 2018). Bifidobacteria are considered beneficial and are thought to confer positive health effects. Hence Bifidobacteria often are the targets for prebiotics, complex carbohydrates that resist digestion in the small intestine and reach the colon where they are fermented by the gut microflora. More research is needed to explore California Prunes’ influence on the gut microbiota and potential to function as a prebiotic.

Research discovered that rats fed a prune diet, at levels equivalent to a 40 g serving, had fewer precancerous colon cancer lesions (aberrant crypt foci) than rats fed the control diet (Seidel D, Hicks K, Taddeo S, Azcarate-Peril M, Carroll R, Turner N. et al 2015). The prune-fed rats also had different distributions of colonic microbiota. Subsequent analysis discovered numerous differences in these compounds based on the location in the colon, the diet (control or prune) and the interaction between the location and diet. Some of the compounds endogenous to prunes were found in animals fed the prune diet but were not detected in the control animals. These included sugar alcohols (mannitol/sorbitol), sugar derived metabolites and other plant-associated compounds. Animals fed the prune diet also had an increase in microbially-derived metabolites suggesting that consumption of the whole fruit delivered a unique combination of prune bioactives to the colon. These results suggest that prunes — either through their endogenous compounds or through microbiallyderived metabolites — change the colon environment, which may have contributed to the reduction of precancerous lesions seen in the earlier work (Seidel D, Taddeo S, Azcarate-Peril M, Carroll R, Turner N. et al 2017).

In a randomized placebo-controlled trials, prune intake significantly decreased hard and lumpy stools while increasing normal stool and not increasing loose and watery stools. Prune intake also resulted in fewer subjective complaints of constipation and hard stools, without alteration of flatulence, diarrhea, loose stools or urgent need for defecation. There were no adverse events or laboratory abnormalities of liver or renal function after prune intake (Koyama T, Nagata N, Nishiura K, Miura N, Kawai T, Yamamoto H 2022).

The fecal microbiome of 143 postmenopausal women ages 55–75 who met the compliance criteria in a randomized controlled trial of a 12-month dietary intervention in one of three treatment groups was characterized at baseline and at the 12-month endpoint. Groups consuming 50 grams or 100 grams of prunes daily showed notable enrichment in bacteria from the family Lachnospiraceae, whereas the control group did not. This group of bacteria has been associated with an ability to decrease inflammatory markers in the body and help maintain the integrity of the gut barrier (Simpson, AMR; De Souza, MJ; Damani, J; Rogers et al 2022.)

Bone protective benefits

Several studies among postmenopausal women, who are at increased risk for osteoporosis, have shown bone-protective effects when consuming about five to six prunes (50 grams) a day. In one of these, study authors noted there was “high compliance and retention” over the 12-month study — in other words, the women in the study enjoyed eating prunes daily and didn’t tend to forget or drop out. In another study, authors said the bone-protective health of prunes in postmenopausal women may be attributed to their unique combination of minerals, vitamin K, phenolic compounds and fiber, which may work together for greater effect.

Prunes’ role in promoting bone health is an active area of preclinical and clinical research in models of hormone deficiency, aging and exposure to certain types of radiation. Strong, healthy bones are the foundation for lifelong vitality and independence. The bone mass attained early in life—around age 30 or so—is an important determinant of bone health throughout aging.

Prunes have nutrients reported to influence bone health including boron, potassium and vitamin K. Prunes’ phenolic compounds are thought to inhibit bone resorption and stimulate bone formation as well as function as antioxidants.

Reviews summarizing the current knowledge on prunes and bone health noted that although the exact mechanism for the protective effects of prunes remains to be determined, it is thought that the additive and/or synergistic effects of prunes’ bioactive phenolics and nutrients are partly responsible (Wallace TC. et al 2017; Arjmandi B, Johnson S, Pourafshar S, Navaei N, George K, Hooshmand S, Chai S, Akhavan N. et al 2017). Preclinical animal and cell studies suggest that prunes and/or their extracts enhance bone formation and inhibit bone resorption through their actions on cell signaling pathways that influence osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation and are consistent with clinical studies that show that prunes may exert beneficial effects on bone mineral density (BMD).

Clinical trials in postmenopausal women:

A 3-month study in 58 postmenopausal women discovered that 100 g (10-12) prunes (75 g dried apple comparative control) resulted in borderline significant increases in biomarkers of bone turnover (Arjmandi BH, Khalil DA, Lucas EA, Georgis A, Stoecker BJ, Hardin C, Payton ME, Wild RA. et al 2002).

A year-long study measured changes in bone mineral density in 100 osteopenic, postmenopausal women consuming 100 g prunes or 75 g dried apple as the comparative control. Participants also received 500 mg calcium and 10 ug vitamin D. Both dried fruit interventions resulted in positive changes from baseline in ulna, spine, femoral neck, total hip and whole-body BMD. However, increases in BMD in the ulna and spine were significantly greater in the prune group compared to dried apple control (Hooshmand S, Chai S, Saadat R, Payton M, Brummel-Smith K, Arjmandi B. et al 2011).

A 6-month randomized control trial in 48 older (ages 65-79) osteopenic, postmenopausal women discovered that consumption of 50 g (about 5-6) prunes may be as effective as 100 g in preventing bone loss in this age group. All participants received 500 mg calcium and 10 ug vitamin D. Total body, hip and lumbar BMD were evaluated at baseline and at 6 months. Biomarkers of bone metabolism and inflammation were also measured at baseline, 3 and 6 months. Both doses of prunes provided bone-protective effects in that there was no net change from baseline in total BMD while the control group continued to lose bone. There was slight but non-significant improvement in lumbar BMD but no detectable differences in the ulna and hip between the groups. Both doses of prunes resulted in lower levels of TRAP 5b, a marker of bone resorption. Thus, results suggest that the bone-protective effects may be attributed to the inhibition of bone resorption with the concurrent maintenance of bone formation (Hooshmand S, Kern M, Metti D, Shamloufard P, Chai S, Johnson S, Payton M, Arjmandi B. et al 2016).

Preliminary findings in a very small follow up study of postmenopausal women who consumed 100 g prunes for one year suggest retention of BMD with prunes. Of the 100 women who completed the initial clinical trial, 20 returned for a follow-up visit: 8 from the prune group and 12 from the dried apple group. Those in the prune group retained BMD of the ulna and spine to a greater extent than those in the dried apple group after 5 years even though they reported no longer regularly consuming prunes. (Hooshmand S, Chai S, Saadat R, Payton M, Brummel-Smith K, Arjmandi B. et al 2011; Arjmandi B, Johnson S, Pourafshar S, Navaei N, George K, Hooshmand S, Chai S, Akhavan N. et al 2017). Overall diet and physical activity were not evaluated in this study and further research is needed to study the extent to which bone density is retained following the cessation of an intervention with prunes.

In a 12-month randomized controlled trials, a 50 g daily dose of prunes prevented loss of total hip bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women after 6 months, which persisted for 12 months. Given that there was high compliance and retention at the 50 g dosage over 12 months, the 50 g dose represents a valuable nonpharmacologic treatment strategy that can be used to preserve hip BMD in postmenopausal women and possibly mitigate hip fracture risk (De Souza MJ, Strock NCA, Williams NI et al 2022).

A 2022 discussion paper highlighted data from preclinical and clinical studies that have assessed the effect of prunes on oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators, and bone outcomes are summarized, and evidence supporting a potential role of prunes in modulating inflammatory and immune pathways is highlighted. Overall, evidence from in vitro, preclinical studies, and limited clinical studies suggest a potential role of prunes with improving bone loss outcomes. These findings may be attributed to components of prunes including minerals, vitamin K, phenolic compounds and dietary fiber working additively or synergistically to inhibit inflammation and oxidative stress, and mediate beneficial effects (Damani JJ, De Souza MJ, VanEvery HL 2022).

Clinical trials in men:

A study suggested that daily consumption of 100 g prunes for 12 months has modest bone-protective effects in men. More research is needed (Hooshmand S, Gaffen D, Eisner A et al 2022).

In another study among 35 men between the ages of 55 and 80, consumption of 100 g prunes led to a significant decrease in serum osteocalcin (p < 0.001) higher levels of which are linked to chronic disease. Consumption of 50 g prunes led to significant decreases in serum osteoprotegerin (OPG) (p = 0.003) and serum osteocalcin (p = 0.040), and an increase in the OPG:RANKL ratio (p = 0.041), an important determinant of bone mass (George KS, Munoz J, Ormsbee LT et al 2022)

Findings from animal studies:

Results in rodent models suggest that prunes can prevent the loss of bone during aging, restore bone that has been lost, promote attainment of peak bone mass, and protect bone from exposure to certain types of radiation. Investigators fed adult and old male mice either a normal diet or diets with 0%, 15% or 25% prune powder by weight for 6 months to determine whether the loss of bone with aging can be prevented and replaced. Bone mass and structure were examined before, during, and after dietary intervention. The diet with 25% prune increased bone volume above basal levels by nearly 50% in the adult and 40% in the old mice and also replaced bone that had already been lost due to aging. Although both adult and old mice responded to the prune intervention, the effects were greatest in the adult mice. The adult, but not the old mice, also gained bone on the 15% prune diet (Halloran B, Wronski T, VonHerzen D, Chu V, Xia X, Pingel J, Williams A, Smith B. et al 2010).

Research also looked at whether 5%, 15% or 25% prune powder by weight could increase bone volume prior to peak bone mass in young, growing mice. Results discovered that bone volume increased by 25%, 49% and 94% respectively. The highest prune intervention – 25% – represents about 20 prunes for humans. The authors noted that because aging seems to blunt response, the equivalent of about 4 prunes a day may be expected to have beneficial effects on bone in children (Shahnazari M, Turner R, Iwaniec U, Wronski T, Li M, Ferruzzi M, Nissenson R, Halloran B. et al 2016).

Investigators looked at the bone-preserving role of prunes when animals were exposed to ionizing radiation, which can increase oxidative damage in skeletal tissues. Such exposure is experienced by astronauts in space, and those receiving radiation therapy as part of treatment for cancer. In this animal study, the interventions included an antioxidant cocktail (vitamins C, E and selenium along with other known antioxidants); dihydrolipoic acid, ibuprofen, and prunes at 25% weight of the diet. The prune intervention was the most effective in reducing undesired bone marrow cells’ responses to radiation compared to the other interventions. In addition, mice on the prune diet did not exhibit bone volume loss after radiation exposure (Schreurs A, ShiraziFard Y, Shahnazari M, Alwood J, Truong T, Tahimic C, Limoli C, Turner N, Halloran B, Globus R. et al 2016).

Based on the bone-preserving properties of prunes’ polyphenols in postmenopausal women and animals, researchers evaluated whether prunes could alleviate the destruction of joints associated with rheumatoid arthritis using transgenic mice that overexpress tumor necrosis factor (TNF), an inflammatory mediator. The research also included a cell study to investigate the anti-inflammatory effect of neochlorogenic acid. According to the Arthritis Foundation, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the joints. This creates inflammation causing tissue that lines the inside of joints (the synovium) to thicken, resulting in swelling and pain in and around the joints (Arthritis.org). Compared to transgenic mice on a regular diet, four weeks of a 20% prune powder diet protected joint bones from destruction in the transgenic mice. This was associated with fewer cells responsible for bone resorption. Neochlorogenic acid, the major polyphenol in prunes, down-regulated the TNF-induced inflammatory mediators in human synovial fibroblasts, which suggests, according to the investigators, that neochlorogenic acid is the bioactive compound in prunes that controls inflammation mediated signaling of osteoclastogenesis. The authors also noted that prunes’ bioactive polyphenols effects on bone anabolism require further study (Mirza F, Lorenzo J, Drissi H, Lee F, Soung D. et al 2018).

Possible mechanisms and bioactive compounds:

While the exact mechanism – or mechanisms – by which prunes support bone health is not thoroughly understood, existing research suggests several possibilities linked to prunes’ nutrient composition and polyphenolic bioactive compounds, which probably act synergistically. Hydroxycinnamate acids represent 98% of the polyphenols currently identified in prunes, with neochlorogenic acid the most abundant (Donovan et al 1998).

Two separate studies were undertaken to identify the most bioactive polyphenolic fractions of prunes on osteogenic activity and their activity under normal and inflammatory conditions. Six fractions of polyphenolic compounds were prepared from a crude extract of prune powder. In each subsequent experiment, 6 polyphenol fractions were tested on cell lines to see which had the greatest potential to either increase the differentiation and function of osteoblasts or decrease differentiation and activity of osteoclasts compared to the control. Initial screening revealed that two fractions had the greatest osteogenic potential. Of the polyphenols known in prunes – chlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, quinic acid, o-coumaric acid, m-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, cyanidin3-rutinoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside, quercetin, rutin, sorbic acid, and 5-hydroxymethyl-2 furaldehyde – only cryptochlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, and rutin were detected in the 2 fractions.

The identified polyphenol fractions were used on bone marrow from mice under normal and inflammatory conditions (by the addition of TNF-α) to further test their effects on expression of genes and proteins involved in osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. Although both fractions were able to suppress osteoclast differentiation and activity, one fraction appeared to have a more robust effect, especially under inflammatory conditions. Both fractions also enhanced osteoblast activity. Treatment with the fractions resulted in a trend for the maintenance of mineralization in the inflammatory environment to the level of the control. However, a higher dose of the fractions or a combination of the fractions might be needed to protect the differentiating osteoblasts from the detrimental effects of TNF-α (Graef J, Rendina-Ruedy E, Crockett E, Ouyang P, Wu L, King J, Cichewicz R, Lin D, Lucas E, Smith B. et al 2017) (Graef J, Rendina-Ruedy E, Crockett E, Ouyang P, King J, Cichewicz R, Lucas E, Smith B. et al 2017).

Research investigating the ability of prunes’ polyphenols, vitamin K and potassium to restore bone in an aged, postmenopausal osteopenic animal model found that the most pronounced effect on restoring bone loss occurred when prunes’ polyphenols were combined with vitamin K and potassium to levels consistent to the amount in whole prunes. The polyphenol extract from prunes was the primary component responsible for 60 to 80% of the effect on bone. Although the study did not focus on the mechanism by which the extract influenced bone, the authors noted that the polyphenols likely contributed to prunes’ antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and/or act at the cellular level to increase early bone cell activity at formation and breakdown. (Graef JL, Ouyang P, Wang Y, Rendina-Ruedy E, Lerner MR, Marlow D, Lucas EA, Smith BJ. et al 2018).

Heart-health benefits

Building on other research, a 2021 study found that postmenopausal women who ate 50 to 100 grams of prunes daily for six months had lower total cholesterol, oxidative stress and inflammatory markers than those in a group that didn’t eat prunes.

Prunes’ nutrient profile can help support heart health. A cholesterol-free food, with no fat, sodium, or added sugars, prunes’ soluble fiber can help manage serum cholesterol levels and potassium can help blunt the effects of sodium in the diet. Men with moderately elevated cholesterol levels experienced a reduction in both total and LDL cholesterol after eating 100 g (10–12) prunes daily, providing about 6-7 g of dietary fiber (Tinker LF, Schneeman BO, Davis PA, Gallaher DD, Waggoner DR. et al 1991).

A mouse study that used prune powder (equivalent to 10-12 prunes) significantly reduced atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta. There was no change in cholesterol levels, suggesting that prunes had a direct effect on the progression of the disease in ways other than lowering cholesterol. Additional research is needed to determine the cause of this effect (Gallaher C, Gallaher D. et al 2009).

A short-term (2 week) crossover study in adult women investigated the incorporation of two snacks daily of prunes or a low-fat cookie (100 kcal matched) on total energy, nutrient intake and biochemical parameters. Neither snack altered energy intake or weight. Total fat and dietary cholesterol intake tended to decrease with prune consumption and compared to cookies, prunes promoted significantly greater intake of fiber, potassium, riboflavin, niacin, and calcium. Plasma triglycerides remained unchanged with prune consumption but was significantly higher after 2-weeks consumption of the low-fat cookies. Although both snacks provided about the same amount of carbohydrates (27 g prunes; 24 g low-fat cookies), which might raise serum triglyceride levels, elevations were detected only during low-fat cookie consumption phase. The authors noted that prunes’ fiber and other nutritive components might have prevented the rise in triglyceride levels compared to the refined carbohydrate snack (Howarth L, Petrisko Y, Furchner-Evanson A, Nemoseck T, Kern M. et al 2010).

Study findings published in 2021 suggest that daily consumption of 50-100 g of prunes improves cardiovascular health risk factors in postmenopausal women as exhibited by lower total cholesterol, oxidative stress, and inflammatory markers (Hong MY, Kern M, Nakamichi-Lee M et al 2021).

In a randomized controlled trial investigating the impact of dried fruit consumer as a snack on food intake, experience of appetite and body weight, phase 1 demonstrated that prune snacks resulted in appetite reduction compared to gummy snacks. Researchers found that those who ate prunes consumed the fewest calories overall at subsequent meals. The prune snackers also reported reduced hunger levels, improved satiety, and a greater perceived ability to eat less food at subsequent meals. Phase 2 demonstrated that prunes did not undermine weight loss, and this warrants further study. Those who consumed prunes also reported higher levels of satisfaction and greater ease of following a weight-loss program (Harrold, JA, Sadler, M, Hughes et al 2021).

Healthy snacking for weight management

Research has shown that eating prunes as a snack can help curb hunger more than a higher carbohydrate snack with the same number of calories. A 2021 study showed that men and women who ate prunes had a reduced appetite as compared to a control group, and snacking on prunes may have contributed to their weight loss – but this needs to be studied further. Overall, the study participants liked snacking on prunes and said it was an easy change to make in their diet.

Prunes are a good source of fiber and have a low Glycemic Index, which can help manage weight through improved satiety and helping keep blood sugar levels stable. Food intake patterns, particularly those that promote satiety without increasing overall caloric intake, play an important role in energy balance and weight management. Population studies reported that the equivalent of 1/8 cup dried fruit intake was associated with lower body weight measures and abdominal obesity (Keast DR, O’Neil CE, Jones JM. et al 2011).

A short-term cross-over study involving healthy men and women investigated whether a preload including prunes consumed as a snack before a meal, compared to an isoenergetic and equal weighed bread product preload would: have greater short-term effect on satiety measured by subsequent ad libitum meal intake; induce greater satiety as assessed by visual analogue scales (VAS); and reduce the appetite for dessert offered shortly after lunch. When participants consumed the preload that included prunes, they consumed less amount of dessert and had lower total energy intake at the meal. Feelings of hunger, desire and motivation to eat as measured by VAS were lower at all time points between the snack and the meal. Participants also had a small energy intake at lunch and ate less of the chocolate cake dessert. Since the macronutrient content of both preloads were similar, the investigators noted that the satiating power of prunes could be due to their fiber content (Farajian P, Katsagani M, Zampelas A. et al 2010).

Healthy women 25-54 years of age participated in a study that assessed responses to two snack choices (prunes and a popular low-fat cookie) matched for macronutrient and sugar contents but differing in fiber. The study measured satiety, subsequent food intake, blood glucose level, insulin and ghrelin responses. Although there was no difference in postsnack consumption between the trials, the satiety index was higher after the prune snack and the rise in plasma glucose and insulin was lower (FurchnerEvanson A, Petrisko Y, Howarth L, Nemoseck T, Kern M. et al 2010). Although not the primary outcome in a study in postmenopausal women investigating prunes’ role in digestive health, women who ate 80 g or 120 g of prunes daily for 4 weeks reported no gain in weight (Lever E et al 2018).

Healthy aging and improved cognition

Several studies have suggested that regularly eating foods high in polyphenols, including prunes, has been associated with “reduced aging in humans and may exert beneficial effects on improving insulin resistance and related diabetes risk factors, such as inflammation and oxidative stress,” according to a 2021 research overview. Another article notes that eating polyphenol-rich foods throughout life “holds a potential to limit neurodegeneration and to prevent or reverse age-dependent deteriorations in cognitive performance.”